Kildorrery

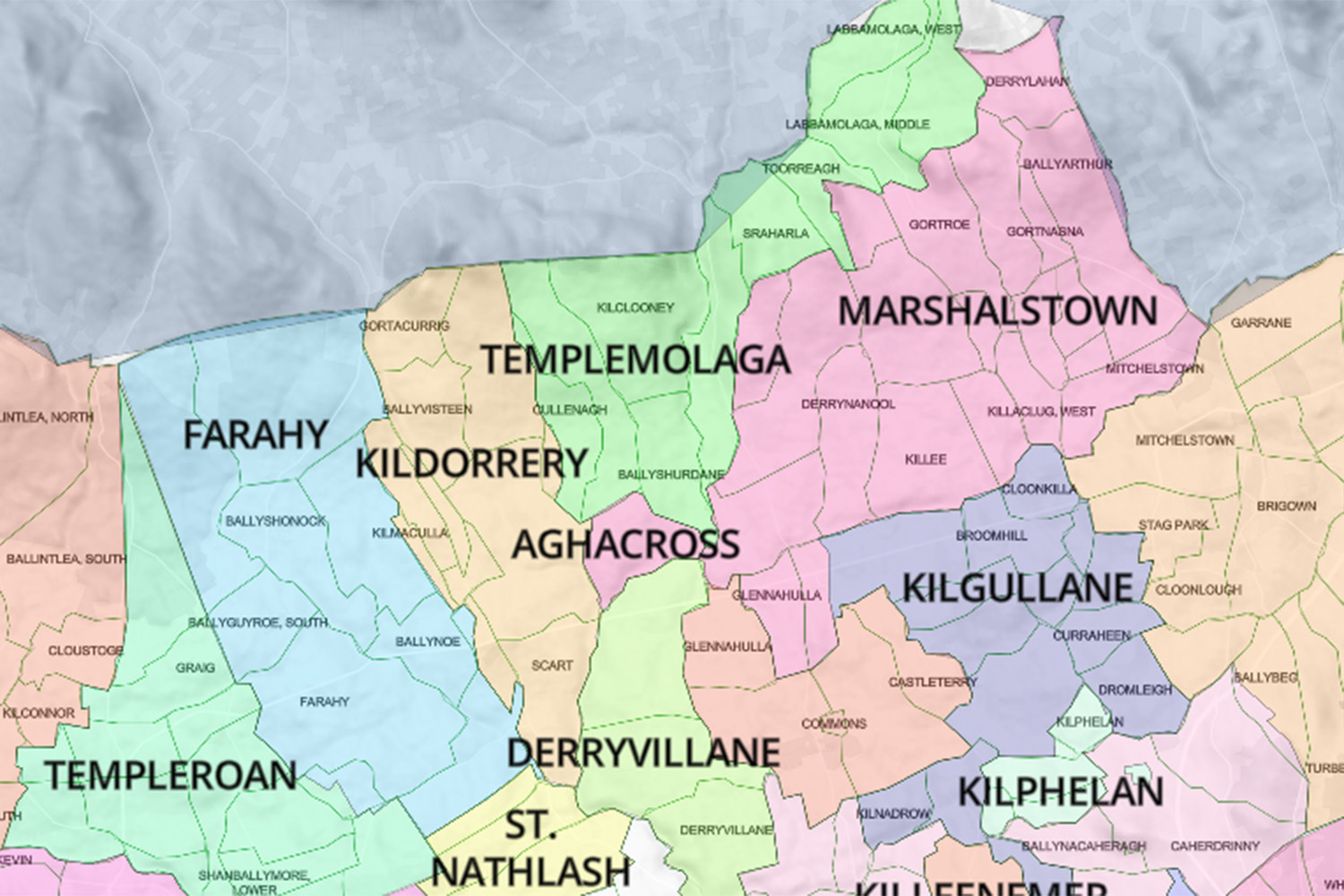

Kildorrery has an area of 18.3 km² / 4,526.5 acres / 7.1 square miles. The modern day R.C. Parish of Kildorrery is made up of 6 medieval parishes called:

While these are still Civil Parishes, they have been in the Kildorrery R.C. Union since parish record keeping began, this is where census and parish records differ, as the census uses the civil parishes listed above except Aghacross, Carraigdownane and Rockmills (St. Nathlash) have been included in Derryvillane.

These parishes are also the reason why we have 6 graveyards in the parish today as each one belonged to its own little medieval parish.

Parish Interactive Map sample

CORK County Civil Parishes Interactive Map

LIMERICK County Civil Parishes Interactive Map

You can switch between both maps on the same page or view other counties by clicking on the county. (Source: johngrenham.com)

The Civil Parishes are broken down into Townlands which are based on an ancient administration system and they still exist today.

The Townlands are most often the key to identifying your ancestors if they came from a rural area as they are listed in the church records in Baptisms and Marriages. They can also be the key to locating a homestead.

There are 11 townlands that we know about in Kildorrery parish. This represents 100% of all the area in Kildorrery.

Oldcastletown (Baile an tSeanchaisleáin)

Springvale (Móin Chrúbáin)

Source: townlands.ie

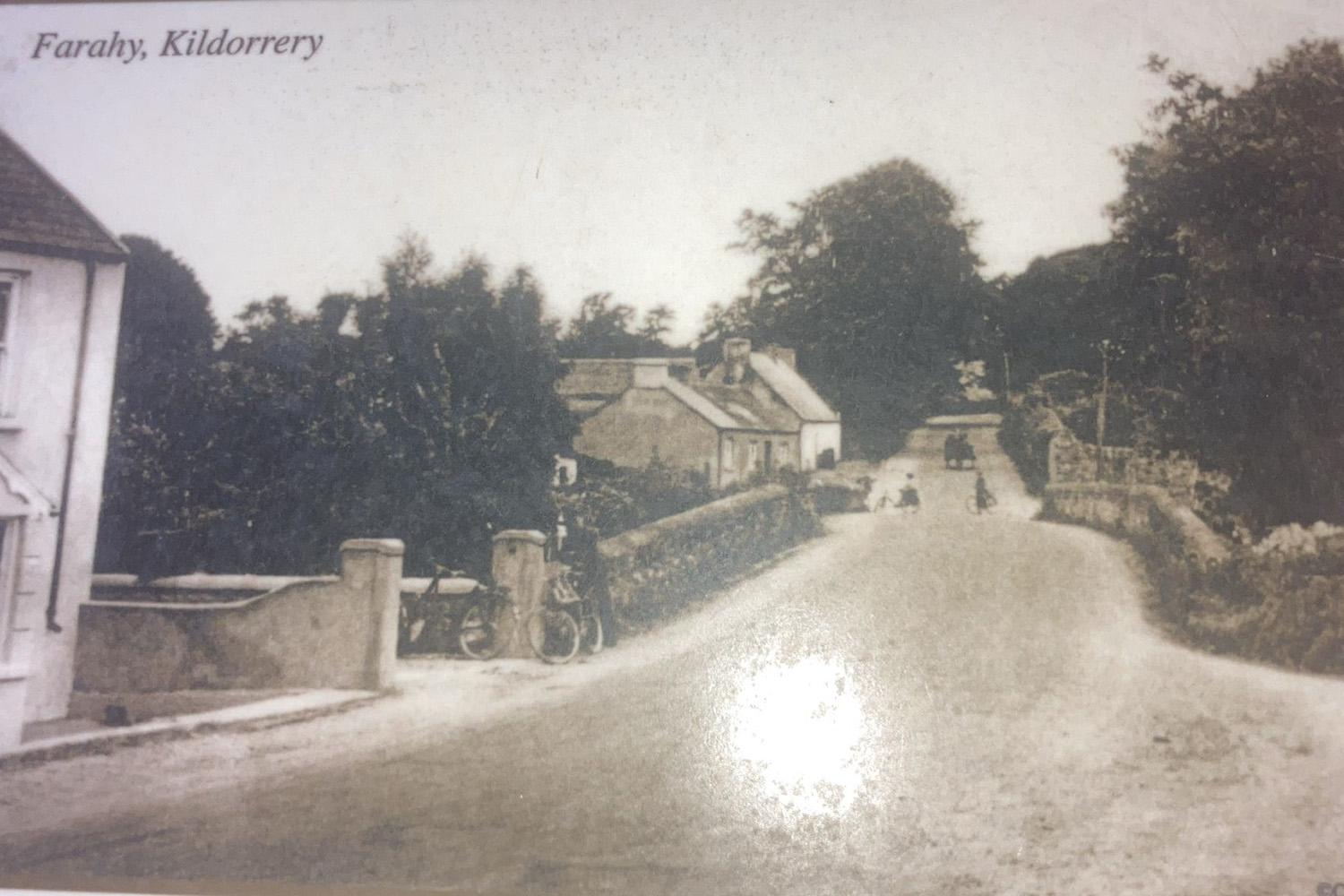

Farahy

St. Colman's Church in Farahy was built in 1721 on the site of a medieval church. Farahy was listed as the seat of the Dean of Cloyne as early as 1225. This seat passed to the established church during the ear of the penal laws and Farahy held this seat until the middle of the 19th century.

The church was built by funds provided by the Bowen family who became the owners of 800 acres in Farahy after the Cromwelian conquest of Ireland. The Glebe house was built nearby and is a private residence today.

See: National Inventory of Architectural Heritage

Townlands.ie: Farahy

The Mass Rock in Farahy became a place of worship during the penal law era but archaeologists believe it may have been a spiritual place going back to the Neolithic era over 4,000 years ago. A park was established around the rock by the local Historial Society to celebrate the millennium year in 2000.

A time capsule was enclosed at the back of the site which contains coins, postage stamps, grains of wheat and many other objects to represent leisure, art and working life in Kildorrery in 2000.

A mass is held there every August to commemorate the suffering of our ancestors.

Aghacross

The substantial ruin of Aghacross Church, founded by Saint Molagga in the seventh century, overlooks the Funcheon River. The existing building has many interesting features, including a weathered carved head of Saint Molagga on the east gable.

Saint Molagga's holy well, on the south-side of the graveyard, has stonework, which may be over 1,000 years old, the well was described in 1936 by Kildorrery children who wrote about it for the Irish Folklore Commission's national schools collection.

'Acts of devotion are performed around the well. The visitors make three or four rounds and recite the rosary while doing so, and the litany of the Blessed Virgin. Visitations are frequently done for headaches, and in this case, the heads are washed in water outside the well. The water of the well has never been used for any domestic purpose. If an attempt were made to boil the water, it would not boil.'

Townlands.ie: Aghacross

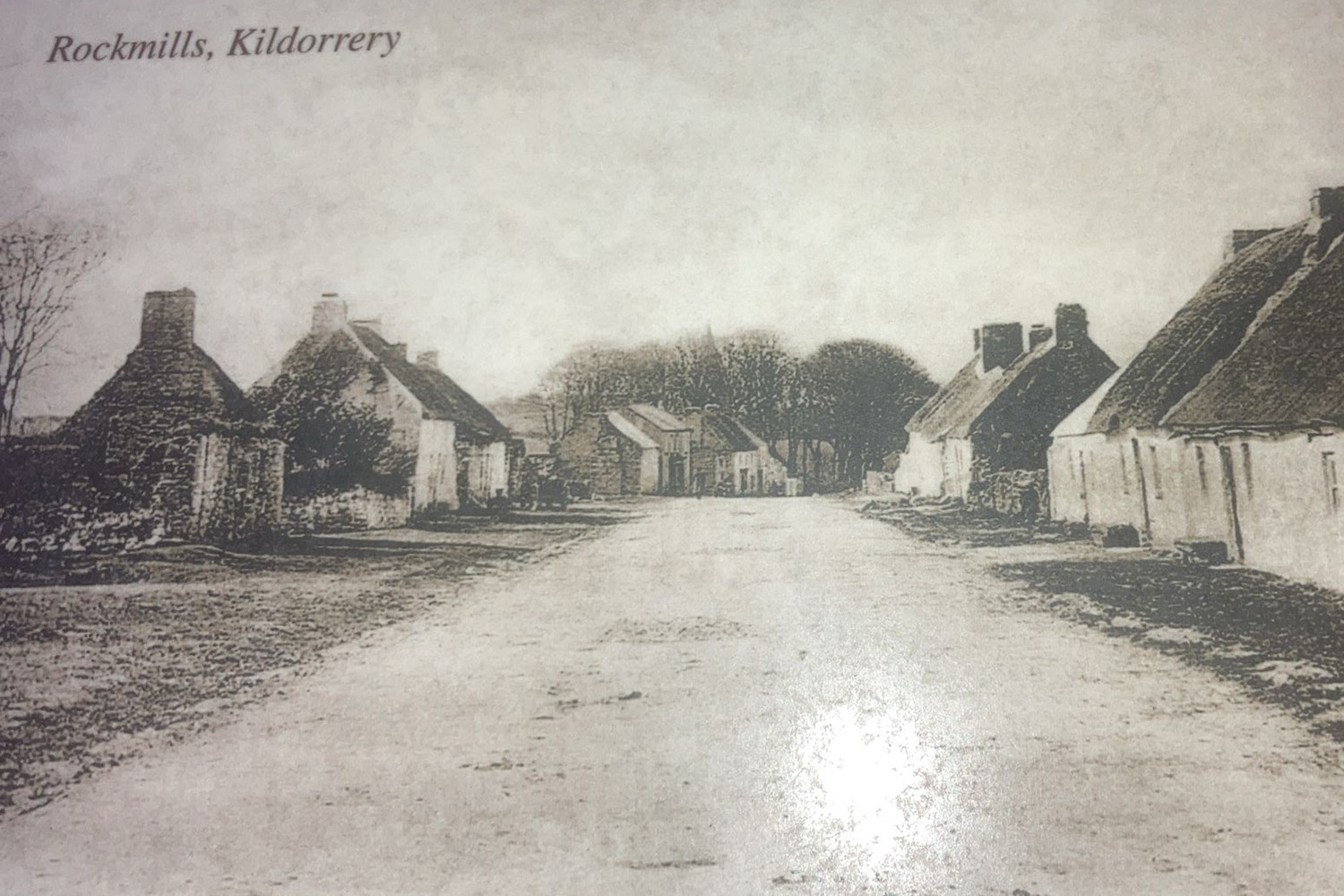

Rockmills

Rockmills (Irish: Carraig an Mhuileann) is a small rural village located in the parish of Kildorrery, in the Avondhu region of County Cork, Ireland. The village derives its name from the large mill that once operated on the banks of the River Funshion, that runs to the east of the village.

Rockmills was once the largest village in the area because of its flourmill. Following a succession of owners the flourmill closed around 1900 and the village gradually lost its population.

The flour mills was the scene of a sharp fight during the Whiteboy risings, when it was attacked to capture the money kept on hands for the purchase of wheat. The assailants were repulsed with the loss of seven lives.

Townlands.ie: St. Nathlash