The History of Kildorrery

Quick Facts

Kildorrery is a village in north County Cork, Ireland. It lies at the crossroads of the N73 road from Mallow to Mitchelstown and the R512 from Kilmallock to Fermoy. These roads were first opened in the early 18th century, the first being a road that linked Clonmel to Doneraile which was soon crossed with a road linking Kilmallock to Fermoy. The streets of Kildorrery were built along these roads pointing them north, south, east and west directions.

Kildorrery has an area of 18.3 km² / 4,526.5 acres / 7.1 square miles. The modern day R.C. Parish of Kildorrery is made up of 6 medieval parishes.

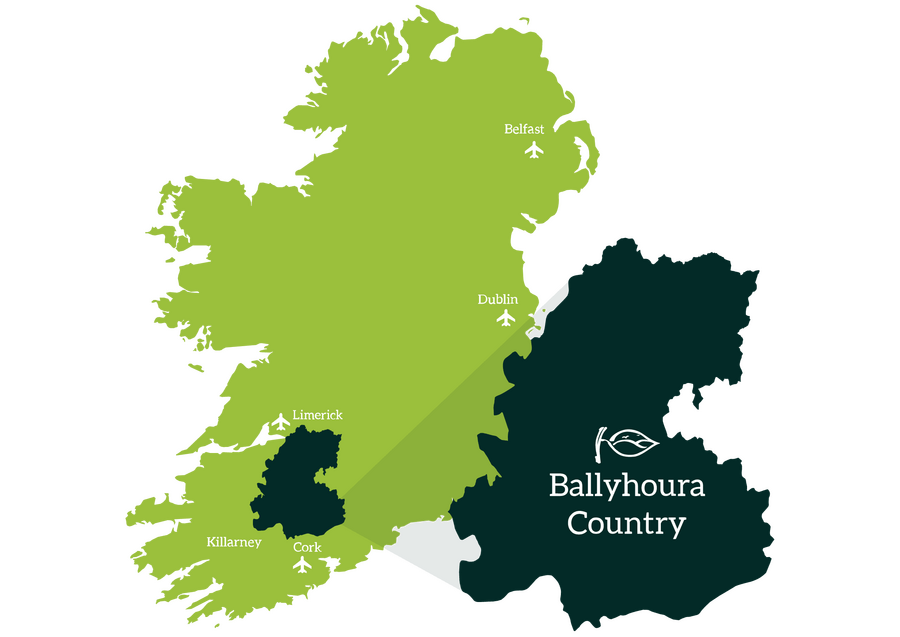

This hilltop village has views to the east of the Galtee Mountains and Knockmealdown Mountains with Slievenamon in the distance. To the north the Ballyhouras – the Limerick road is flanked by two mountains, Castlegale and Carrigeenamronety (Carraigín na mBróinte). To the south, across the Blackwater Valley are the Nagle mountains, and to the west towards County Kerry the Paps are sometimes visible.

In summer, the village hosts an annual festival fundraiser (affectionately known as 'Hillfest'), which sees a variety of live music and tribute bands (Qween, The Fogues, ABBAesque, Trevor Smith 'Garth Brooks' Experience, Thin Lizzy), local acting talent, family-friendly activities and most recently in 2023 and 2024, 'Cork's Fittest Superstars', hosted by Davy Fitz of Ireland's Fittest Families fame. Kildorrery celebrated its 50th anniversary of Hillfest in 2022 with tribute band ABBAesque, popular country folk singer Mike Denver, as well as a skit by local talents that captured the highlights of the last 50 years. The festival is organised and run by a small group of dedicated volunteers and well supported by the local and neighbouring communities.

Agriculture, including dairy farming, provides much of the local employment. The village itself is well supplied with a variety of businesses, including a large petrol station, a well-stocked grocery shop, a fast food outlet, a bus/coach transportation service, a top-rated restaurant cafe, two lively pubs with frequent live music, several hair salons and beauticians, home bakers, craftsmen, sign makers/printers, mechanics, vets, kennels, horticultural businesses, a national haulage firm, a funeral parlour and a nursing home.

Kildorrery National School was opened in 1977, an amalgamation of Ballinguyroe and Scart National Schools. Kildorrery NS is a co-educational, Catholic Primary School. There are ten full time teachers, one part time teacher and four Special Needs Assistants in the school. There are 195 pupils on roll as of 2022/23. Kildorrery also has a pre-school, It's All About Kids, located in a community hall within the grounds of the church.

Origins

The village of Kildorrery owes its origins to a church, mentioned in 1507, the papal taxation records of Pope Boniface VIII. Kildorrery began as a market town in 1606, when King James I granted a licence to Maurice Fitzgibbon, the White Knight of Oldcastletown to hold a fair on the eve of St. Bartholomew’s day (24th Aug).

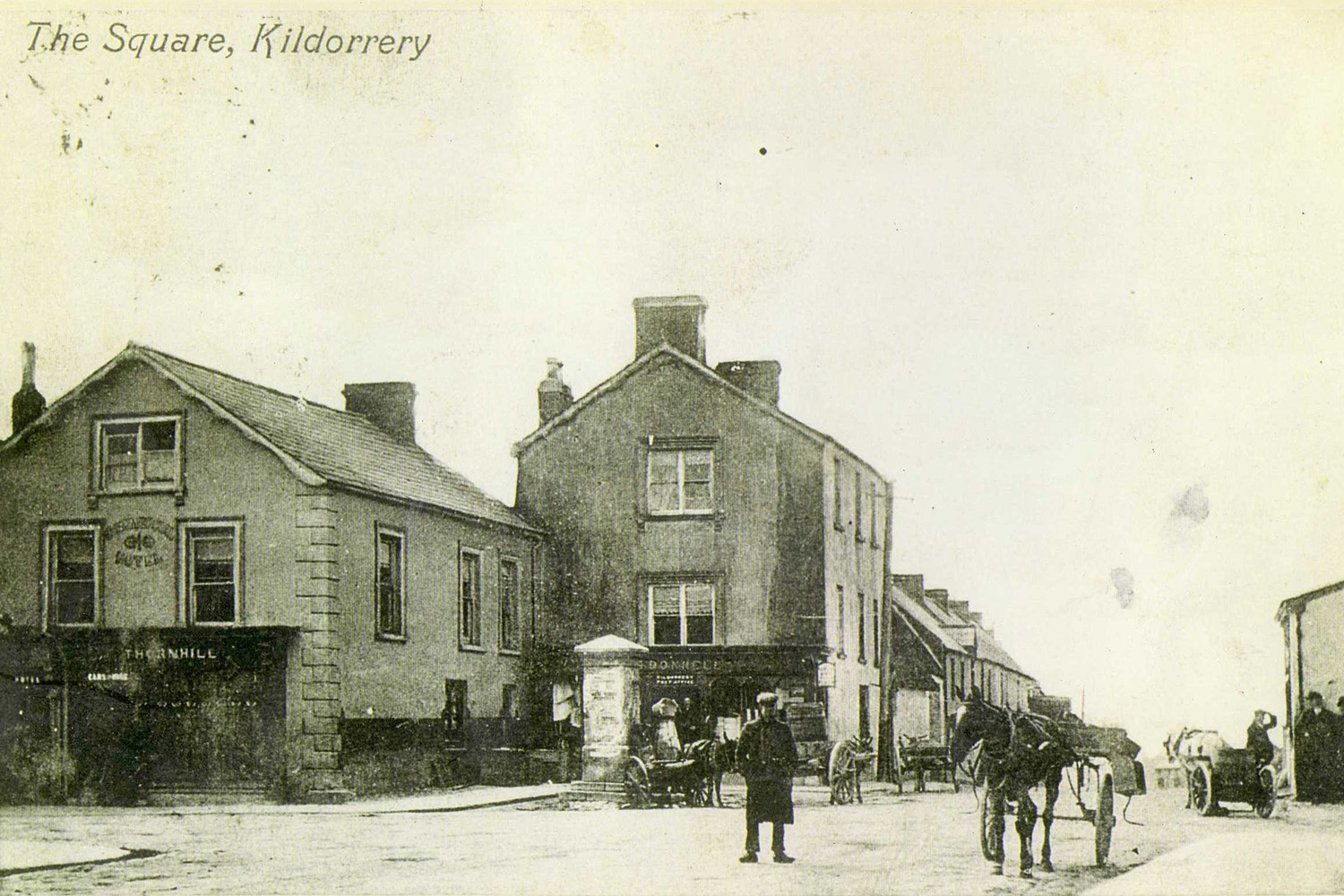

The village we see today originated in the 1780’s when Robert the 2nd Earl of Kingston began a lifelong project of developing his 100,000 acre estate which involved demolishing whole villages and replacing them with wide urban streets with two storey houses for his tenants. By 1837, Kildorrery had 90 houses, a constabulary barracks and a medical dispensary. Fairs for selling cattle, sheep and pigs were held in May, June, September and November. St Bartholomew's parish church was built in 1838.

Kildorrery from the air, 2023 (Photo Credit: Tom Thornhill)

Main Street late 19th century

Main Street 2020 (Photo Credit: Mícheál Collins)

Meaning 'The Striped Mountains', The Ballyhoura Mountains run east west for about 12 km along the county boundary between Cork and Limerick. Its highest point is Seefin Mountain, Suí Finn (528m). The name Suí Finn translates as the Seat of Fionn (Mac Cumhaill). It is so named because, according to tradition, Fionn mac Cumhaill and the Fianna stopped here in their travels around the country.

These hills now peacefully divide the neighboring counties of Cork and Limerick but over 1,000 years ago were the dividing line between the Provencal Kingdoms of Tuadmumu (North Munster) and Desmumu (South Munster) who were often at war with each other.

The Cross of Redchair, Bearna Deargh marks the county boundary. The road runs through what was once a well known area as it was there that Brian Boru’s brother ‘Mahon’ who was then King of Munster was slain by a Norseman, ’Maelmaud’. Brian then became king of Munster and swore vengeance for his brother’s death. Eventually Brian and his armies defeated the Norsemen and the Danes in 1014 at The Battle of Clontarf.

Over 600 years later, in the mid 17th century the Cross of Redchair was remembered for a trick played on the Lord President St. Ledger by the rebel Lord Mountgarret, then one of the most wanted men in Ireland. St. Ledger had amassed his troops to ambush Mountgarret and his insurgents on their way through the narrow pass. Mountgarret calmly entered the pass, approached St. Ledger and produced to him a forged letter which he claimed was issued by the King offering him free passage throughout the country. St. Ledger rather foolishly took the letter as being authentic, left Mountgarret through, disbanded his forces and retired for the evening.

Explore the Ballyhouras: https://visitballyhoura.com/

An Claidh Dubh or the Black Ditch is an ancient linear earthwork running a distance of over 22kms from the Ballyhoura Mountains to the Nagle Mountains crossing the Blackwater valley in North East Cork. Similar earthworks can be found in other parts of Ireland most notable the Black Pig’s Dyke which formed the border of the ancient Kingdom of Ulster. These Ditches date back over 1,000 years and it is believed they were modelled on Ancient Roman Limes, their defensive boundaries such as Hadrian’s Wall between Scotland and England.

In 1998 an archaeological survey of the entire Ditch and a partial excavation revealed much more of what it looked like and what its purpose might have been. The earthworks consisted of an earthen bank with a ditch on either side with the bank varying in width from 4 to 9 meters and up to 1.8 meters in height. It was topped by a thick thorny hedge and in some places a substantial timber palisade. In places at the sides there were shallow trenches which would have filled with water.

Archaeologists also discovered that a 2 meter surfaced track ran parallel to the eastern side of the ditch. This Ditch was described in an ancient manuscript called ‘Crichad an Chaoilli’ (the Ancient Kingdom of Fermoy) which forms part of the ‘Book of Lismore’ and is dated to before the Anglo-Norman invasion of the 12th century. In this manuscript, as translated by Patrick Power in 1932, the Ditch is described as a dividing line of the local Kingdom, suggesting its construction would indicate a period of social unrest, territorial disputes, etc., but this structure was not massive enough to resist a full scale territorial invasion but would certainly have discouraged wandering livestock or casual ‘cattle rustling’.

The Claidh Dubh is by now mostly indistinguishable from the surrounding countryside and field boundaries but can be viewed from the roadside in places and from satellite images if you know what you are looking for. The most remarkable fact about the Claidh Dubh today is that it forms part of the boundary between Kildorrery and neighboring parish of Shanballymore and several other townlands and parishes as it twists its way through the countryside. This suggests that the local boundaries we know today are more ancient than we can imagine.

View photos on these websites:

https://www.activeme.ie/guides/claidh-dubh-the-black-ditch/

https://visitballyhoura.com/explore/an-claidh-dubh-the-black-ditch

Saint Molaga, who lived in the 6th century, founded churches in Aghacross and Labbamolaga. These early ecclesiastic sites are of enormous interest to archaeologists because its association with the saint links them to the early Christian era in Ireland.

Many archaeological excavations have been carried out on these sites and have had remarkable revelations. Saint Molaga’s ‘Betha’ (Life-story) was written in a church called ‘Tullagh Mien’ about 400 years after his death. That church is believed now to have been near where Sraharala Church is today.

Saint’s Bethas have often been dismissed by historians for being empty of historic fact and instead concentrating on myth and miracles associated with their subjects, but recent studies of Molaga’s Betha and comparisons’ found in Crichad an Chaoilli reveal more historic fact than previously agreed.

One such fact was the description of Molaga’s Thermon or Sanctuary which is bordered to the north by Labbamolaga Church where the Saint is said to be buried, and to the south by the river Funcheon where the ruin of the other church associated with the saint stands in Aghacross.

Ringforts are the most widespread archaeological field monument in the Irish countryside. There are over 30 Ringforts in the Parish of Kildorrery.

They are usually known by the name of ‘Rath’, ‘Lios’ or ‘Dún’ and form a part of many place names in Ireland. Kildorrery was listed as ‘Lios an Cunic’ in a 12th century topographical manuscript called ‘Crichad an Chaoilli’ meaning ‘The Kingdom of Fermoy’. This suggests that Kildorrery was then a fortified hill of strategic importance.

The Ringfort is a circular or roughly circular area enclosed by an earthen bank formed of material thrown up from a central fosse (or ditch) on it’s outside. Generally the diameter of the enclosure is between 25 m and 50 m. These sites are not “forts” in a strict military sense; many are overlooked by higher ground and the number of rings of defence may reflect on the status of the site or its occupier rather than constitute a strengthening of its defences. This is confirmed in the Early Irish laws, which describe larger sites as the home of kings, with the less impressive sites with the lesser ranks of society.

Archaeological excavation has shown that the majority of Ringforts were enclosed farmsteads built in early Christian times. Radiocarbon samples have fairly consistently provided a date range during the second half of the first millennium but this is in constant debate as some archaeologists argue that these sites date back to the Iron Age and were abandoned, reoccupied and modified as required over the centuries. The earthworks acted as a defence against natural predators like wolves as well as the local warfare and cattle raiding that was common at the time.

The Ringforts were gradually abandoned in the decades following the Anglo-Norman invasion of the 12th century as the Normans introduced the building of stone castles and the Irish soon followed. There is a cluster of the remains of 3 ringforts to the eastern end of the village which are still visible today.

‘Crichad an Chaoilli’ (The Kingdom of Fermoy) is a 15th century manuscript contained in the ‘Book of Lismore’. It is a copy a 12th century topographical tract which describes the north east Cork area before the Norman invasion in 1169. It is unique as it is the only tract of its kind in Ireland which not only describes the administrative units (but also lists the churches, burial grounds and the local Chiefs (Tuiseach na Túaithi) and other main Gaelic families who were soon to be ruled by the Norman conquerors. It is likely that it was originally written for the benefit of taxation due to the detail of information it contains. This information has now enabled historians and archaeologists to construct a map of the region in the pre-Norman era.

The Kildorrery region of today is described as being divided into 3 ‘Túatha’ which are roughly similar to the modern day civil parishes of the area and they are in turn broken down into ‘Bailte’ which are similar to the townlands of today.

The 3 Túatha listed are:

Túath Uí Chuscraid (Kildorrery, Aghacross and part of Templemolaga).

Túath Uí Chuscraid Sléibe (Templemolaga, Derryvillane, parts of Marshallstown, Kilgullane and Mitchelstown).

Túath Uí nDuinnin (Farahy, Rockmills and Carraigdownane)

In Kildorrery Graveyard are the ruins of the Medieval Parish Church of Kildorrery (Cill Dairbhre 'Church of the Oaks') probably on the site of a wooden church as the name suggests. The church is dedicated to St Bartholomew and is listed in the 1291 Papal Taxation. The church was burnt in 1321 due to a local dispute and was reported as 'deserted' in 1591, not long after the King of England, Henry VIII, set about taking over the religious buildings in Ireland. Although the church was back in repair by the early 17th century, a few decades later it had fallen into ruin again following the turbulence of the 1641 Rebellion.

This church is built of rubble red sandstone and is set on the traditional Christian alignment of east-west, facing east toward the rising sun, symbolic of the risen Lord. It is divided into a nave to the west and a narrower and shorter chancel to east.

Recent archaeological investigations, as part of ongoing conservation work by Cork County Council, has uncovered evidence that the church was built in a distinctive Irish style known as the 'School of the West', which is a transitional style between Romanesque and Gothic, dating to around 1200. This style suggests a church of some distinction, with skilled sculptors employed in its construction.

Like most medieval parish churches in Ireland this church was extensively refurbished in the 15th century. The door with the pointed arch in the south wall belongs to this period. This alteration was common to allow for accommodation at the western end of the church for the priest to live in. Internal redecoration was also extensive here; only a single foliage-decorated capital from the earlier church was left in its original position. Many of the carved stones were reused, for example the carved roll-moulding around a wall niche in the north wall of the chancel. Others were used as grave markers and many other carved stones were found during conservation work.

There are two interesting carved heads in the church, one inserted over the door and the other inside; a third fragment of a head was found in rubble during conservation works. These heads are probably part of the earlier 13th century church.

The graveyard here probably dates from the first church. It is not unusual that no headstones earlier than the 18th century exist, as it was not until this time that the practice of erecting headstones or grave markers became more common. The graveyard is still in use to this day and visited as a place of prayer and remembrance. The graveyard and church are archaeological monuments (CO018-047002 and CO018-047001, respectively).

Kildorrery is a place that is steeped in heritage and the pretty village has a strong line of attractive two story buildings. One of the oldest residential buildings in the town is the Thatch and Thyme, located on the south-eastern end of the main street. Here one can learn more about the history of Kildorrery and the Heritage and Wildlife Trails that exists in the area.

The Anglo-Norman Fitzgibbon Clan came to Ireland from Wales in the 14th century and quickly established themselves in the area owning lands which covered a large area extending across North Cork, South Limerick and Tipperary. They built castles in Kilbehenny, Kilmallock, Mitchelstown, Ballyhea and in Oldcastletown, Kildorrery. Most of their recorded history is one of war with their neighbours, at first the McCarthys of Desmond (a Gaelic Irish Family who they would subsequently marry into) and later the Lord Roche of Glanworth with whom they developed a murderous rivalry.

They lasted here for 12 generations until Sir Edmund Fitzgibbon (the last effective White Knight), who was said to be a treacherous, double-dealing, ‘stab you in the back’ sort of chap who regularly changed sides to suit his own needs. He was related to the most wanted man in Ireland, the Earl of Desmond, who he turned over to the English Crown for a reward. He died a day after his son in 1608 and it is believed they were poisoned by a member of their own family. The last heir died as a boy three years later and their lands went to his eleven year old niece Margaret who was a ward of the Governor of Ireland and was promptly married off to his nephew (Sir William Fenton) placing the lands firmly in English hands.

The Castle of Oldcastletown 16th Century

The White Knight’s Castle of Oldcastletown was built in the 16th century by William Caoch (‘TheBlind’) Fitzgibbon who was the son of John Fitzgibbon the 5th White Knight and brother to Maurice Fitzgibbon the 6th White Knight. It was built on a rock outcrop known as ‘Magner’s Rock’ which was the site of a former building which gave the name ‘Bally an tSean Caisleán’ to the District. The building was once said a five storey tower house but was badly damaged by Cromwell’s sidekick Lord Broghill during his assault on it in 1650. The next known occupants of the site were the ‘Fennels’ who built the more modern styled country house which is the ruin that you see today and they became known locally as the ‘Dogboys of the Bowen’s’.

When Sir William Fenton married Margaret Fitzgibbon they inherited the vast estate of The White Knights. Their male heirs both died young and so the estate was inherited by their daughter Catherine who married John King and thus began a family story which lasted over 300 years which is brilliantly recalled the book ‘White Knights, Dark Earls – the rise and fall of an Anglo-Irish Dynasty’ by historian Bill Power. John King had been an officer in Oliver Cromwell’s army and like many others were put into positions of power in Ireland after the Cromwellian conquest and subsequent plantation.

Robert King (1754-1799) became the 2nd Earl of Kingston when he married his cousin Lady Caroline Fitzgerald (1755-1823) who had inherited the 100,000 acre Kingston estate in Munster. It is their legacy which is most visible today in the area as Robert inspired by their ‘Grand Tour of Europe’, began building projects on his estate which saw the rebuilding of the villages and the development of much of the Mitchelstown that can be seen today including Kingston College and Market Square which are regarded as the finest examples of Georgian architecture to be seen in Ireland. They were also insightful in that the hired the famous English agriculturalist Arthur Young to manage the estate lands and he introduced many projects like tree planting and the general improvement of farming practices.

Their son George (1771-1839) became 3rd Earl of Kingston when he inherited the estate. He is described as being a megalomaniac with grandiose ideas. His first act on inheriting the estate was to pull down the 50 year old Georgian mansion his father had built and in its place build the largest neo-gothic house in Ireland known as Mitchelstown Castle. The scale and grandeur of the project near bankrupt the estate but nothing stood in the way of ‘Big George’s’ extravagance. The castle dominated the local landscape for the next 100 years before it was burnt down in the Civil War in 1922.

St. Bartholomew's Church was built in 1838 and opened for divine worship the following year. A marble plaque on the east wall of the nave commemorates Rev. Fr. J. Golden who built the church and is buried beneath. Many alterations and additions have been made to the church over the years which have greatly enhanced its overall appearance. Along with the alterations shown below several others were also made over time inside and outside.

The first major restoration was carried out in 1911. During a later restoration a piece of timber was found concealed in the reredos which had a note scribbled on it with the names Thos. Finn, Kildorrery, Carpenter and John McGuire, Cork. It also stated that 'this church was overhauled in its seventy-first year'.

The 14 Stations of the Cross were added in 1918. The original belfry was taken down and a new one constructed from the ground up between 1928 and 1930. The bell was also replaced at this time. The terrazzo passages were put down in 1934 and the original stone flagged floor was covered in pitch pine. In 1936 the central heating was installed and a clock was purchased for the back gallery. The clock cost £12 - a sizeable sum at that time.

Between 1995 and 1998, Canon Twomey, former Parish Priest, spearheaded a major renovation project for the church. This included re-roofing of the building, repair of the belfry, re-plastering of the walls, rewiring and the fitting of new lights, painting and carpeting. A new carpet was donated for the Sanctuary and laid by Mick Fitzgibbon of Quitrent, who also supplied the carpet for the Sacristy and Prayer Room. Sean Dennehy upgraded the lights inside and new chairs were purchased for the Prayer Room from Rockmills Furnishings in Kildorrery. A new burner was installed in the heating boiler and the clock, installed in 1902 on the back gallery, was restored by Stokes Ltd, McCurtain St in Cork. The Sanctuary Lamp was cleaned and re-guilded by a silversmiths firm in Cork.

The structural changes included the conversion of the mortuary into reconciliation rooms, erecting a fire screen across the back of the church with a crying room at the back corner and building internal stairs to both side galleries. All the windows were re-leaded and the frames replaced. The floor was sanded and sealed.

Liam Feehely Limited of Rathcooney Road, Cork, was contracted to undertake the work. They are well known for their work on churches in Ballincollig, Rochestown, Douglas and Mallow, to name a few. They are also specialists in large buildings of architectural importance containing intricate plasterwork, such as AIB South Mall Cork and the Imperial Hotel in Cork.

The renovation project finished in November 1998 with the painting of the church, using a rubber based mix that will better withstand the elements.

The Irish Potato Famine, also known as the Great Hunger, began in 1845 when a mold known as Phytophthora infestans (or P. infestans) caused a destructive plant disease that spread rapidly throughout Ireland. The infestation ruined up to one-half of the potato crop that year, and about three-quarters of the crop over the next seven years. Because the tenant farmers of Ireland—then ruled as a colony of Great Britain—relied heavily on the potato as a source of food, the infestation had a catastrophic impact on Ireland and its population. Before it ended in 1852, the Potato Famine resulted in the death of roughly one million Irish from starvation and related causes, with at least another million forced to leave their homeland as refugees.

Ireland in the 1800s

With the ratification of the Act for the Union of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801, Ireland was effectively governed as a colony of Great Britain (until the Irish War of Independence ended in 1921). Together, the combined nations were known as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

As such, the British government appointed Ireland’s executive heads of state, known respectively as the Lord Lieutenant and the Chief Secretary of Ireland, although residents of the Emerald Isle could elect representation to the British Parliament in London.

In all, Ireland sent 105 representatives to the House of Commons—the lower house of Parliament—and 28 “peers” (titled landowners) to the House of Lords, or the upper house.

Still, it’s important to note that the bulk of these elected representatives were landowners of British origin and/or their sons. In addition, any Irish who practiced Catholicism—the majority of Ireland’s native population—were initially prohibited from owning or leasing land, voting or holding elected office under the so-called Penal Laws.

Although the Penal Laws were largely repealed by 1829, their impact on Ireland’s society and governance was still being felt at the time of the Potato Famine’s onset. English and Anglo-Irish families owned most of the land, and most Irish Catholics were relegated to work as tenant farmers forced to pay rent to the landowners.

Ironically, less than 100 years before to the Famine’s onset, the potato was introduced to Ireland by the landed gentry. However, despite the fact only one variety of the potato was grown in the country (the so-called “Irish Lumper”), it soon became a staple food of the poor, particularly during cold winter months.

Great Hunger Begins

When the crops began to fail in 1845, as a result of P. infestans infection, Irish leaders in Dublin petitioned Queen Victoria and Parliament to act—and, initially, they did, repealing the so-called “Corn Laws” and their tariffs on grain, which made food such as corn and bread prohibitively expensive.

Still, these changes failed to offset the growing problem of the potato blight. With many tenant farmers unable to produce sufficient food for their own consumption, and the costs of other supplies rising, thousands died from starvation, and hundreds of thousands more from disease caused by malnutrition.

Complicating matters further, historians have since concluded that Ireland continued to export large quantities of food, primarily to Great Britain, during the blight. In cases such as livestock and butter, research suggests that exports from Ireland may have actually increased during the Potato Famine.

In 1847 alone, records indicate that commodities such as peas, beans, rabbits, fish and honey continued to be exported from Ireland, even as the Great Hunger ravaged the countryside.

The potato crops didn’t fully recover until 1852. By then, the damage was done. Although estimates vary, it is believed as many as 1 million Irish men, women and children perished during the Famine, and another 1 to 2 million emigrated from the island to escape poverty and starvation, with many landing in various cities throughout North America and Great Britain.

Legacy of the Potato Famine

With a population significant reduced by 2 to 3 million, and increased food imports after 1850, the Irish Potato Famine eventually ended around 1852. But for those who remained behind in a decimated Ireland, a renewed appreciation was ignited for Irish independence from British rule.

The exact role of the British government in the Potato Famine and its aftermath—whether it ignored the plight of Ireland’s poor out of malice, or if their collective inaction and inadequate response could be attributed to incompetence—is still being debated.

However, the significance of the Potato Famine (in the Irish language, An Gorta Mor, or “the Great Hunger”) in Irish history, and its contribution to the Irish diaspora of the 19th and 20th centuries, is beyond doubt.

Tony Blair, during his time as British Prime Minister, issued a statement in 1997 offering a formal apology to Ireland for the U.K. government’s handling of the crisis at the time.

Irish Hunger Memorials

In recent years, cities to which the Irish ultimately emigrated during and in the decades after the event have offered various commemorations to the lives lost. Boston, New York City, Philadelphia and Phoenix in the United States, and Montreal and Toronto in Canada, have erected Irish hunger memorials, as have various cities in Ireland, Australia and Great Britain.

In addition, Glasgow Celtic FC, a soccer team based in Scotland that was founded by Irish immigrants, many of whom were brought to the country as a result of the effects of the Potato Famine, has included a commemorative patch on its uniform—most recently on September 30, 2017—to honor the victims of the Great Hunger.

A Great Hunger Museum has been established at Quinnipiac University in Hamden, Connecticut as a resource for those seeking information on the Potato Famine and its impact, as well as for researchers hoping to explore the event and its aftermath.

Source: History.com

The British authorities started keeping population records in 1800 and the local population declined at 10% per decade throughout the 19th century except from 1840-50 when it increased to 30% due to the Great Famine. Population decline continued for 160 years until it started to gradually but steadily climb for the first time on record through the 1960s.

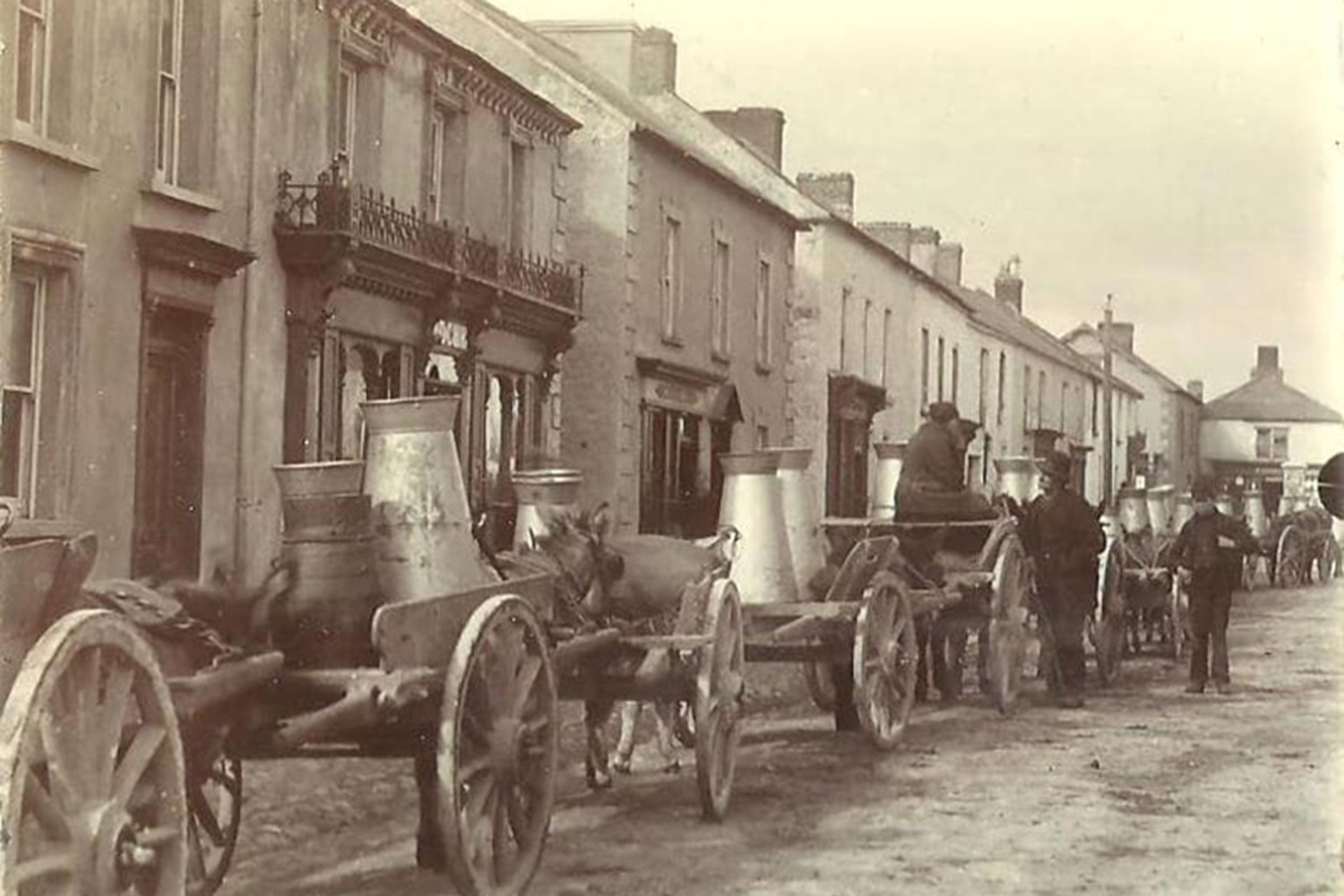

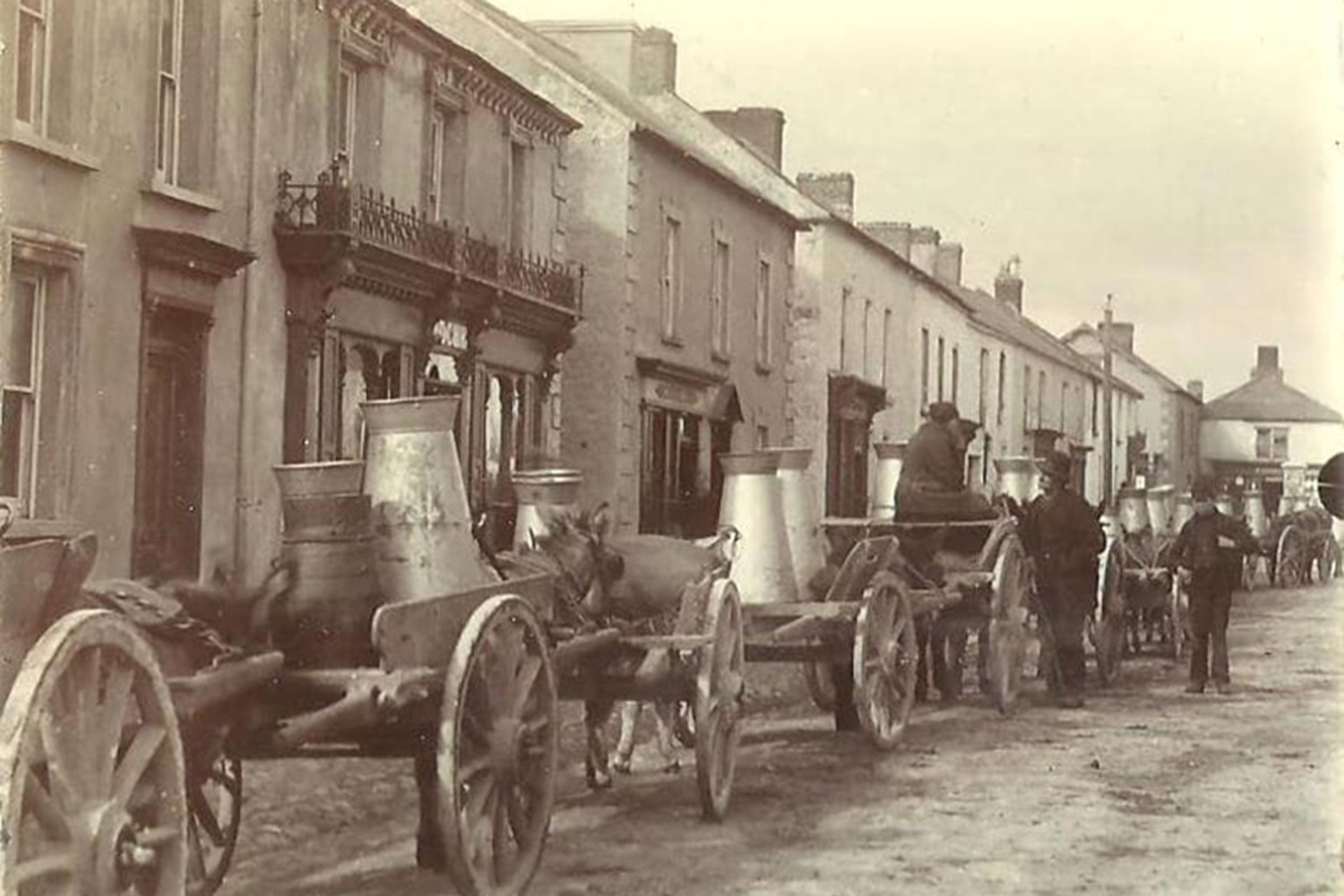

By the late 19th century Kildorrery had a well established local economy based principally on agriculture and mainly on the dairy sector. There were privately owned creameries in the area who bought milk from the Farmers and turned it into salted butter which was then transported to Cork where it was exported to Britain.

By 1875 the village was a hub of economic activity with 10 Grocers and 11 Vintners listed in Guy’s Directory and also several other businesses such as: Butchers, Coal Merchant, Flour and Meal Dealer, Bakers, Drapers, Blacksmiths, Leather Seller, Seed Seller, Cooper, Saddle Maker, Tailors, Dress Makers and Cobbler. The village also had a Hotel, a part-time Bank and a Post Office with a telegraphy service. No doubt these businesses were supplying the many farming families in the locality. There were also 4 schools in the area, Scart, Graigue, Sraharla and Ballinguyroe.

For many centuries fairs were an important part of rural life as it provided local farmers with the opportunity to sell and trade their livestock and other produce. The first fair held in Kildorrery was in 1606 when James 1 granted Maurice Fitzgibbon of Oldcastletown a licence to hold a fair on the 24th August the eve of St. Bartholomew’s Day. By the 19th century Kildorrery was well established as a Fair village with cattle and horse fairs being held on the 1st of May, 27th of June, 3rd of September and the 27th of November. Pig fairs were held on the first Wednesday of every month with a butter, fowl and general market every Wednesday.

Kildorrery was particularly famous for its horse fairs in the early 19th century a time when horses played a huge role in everyday life as they provided transport, labour and of course as they do today, sport. Kildorrery Horse Fair was described by an Irish contributor to a British Sporting Magazine in 1837 as being the best horse fair in Britain or Ireland with “plenty of amusement for the lovers of “fun and frolic”. He also described one of the main events of the day being a Sweepstakes Horse Race with up to sixty riders in which “many a collar bone would be cracked in the desperate riding which can decide such an affair”.

Faction fighting was also then a popular ‘sport’ and was part and parcel of a fair. These fights were once common throughout Ireland in the 19th century and were contested between rival families or parishes, with up to 500 supporters on each side who carried blackthorn sticks as their weapon of choice. Fairs in Kildorrery continued right up to the middle of the 20th century but would eventually make way for cattle and sheep marts, and horses were replaced by tractors on the farm.

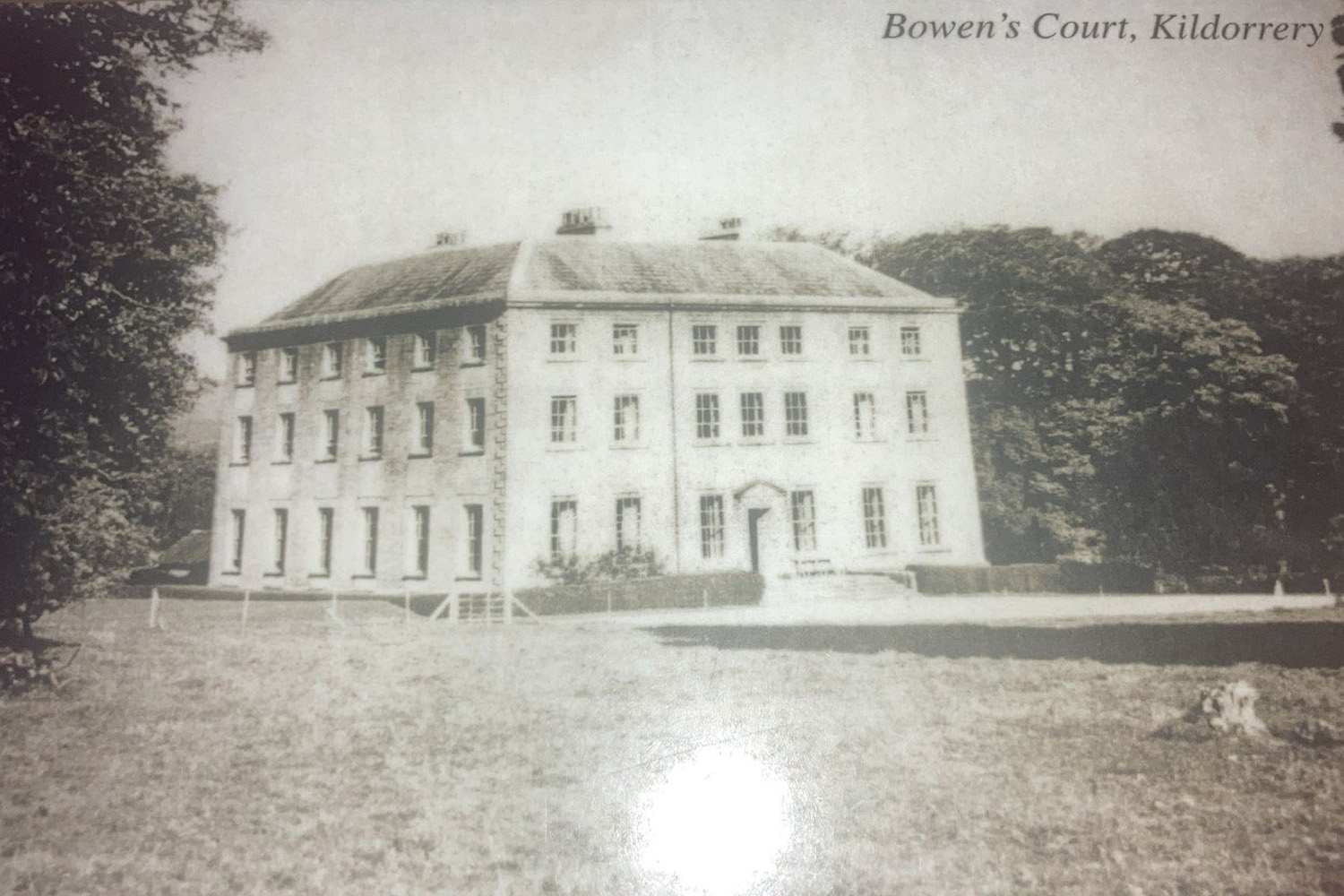

For almost 200 years, Bowen's Court skimmed the Farrahy skyline. Situated below the village of Kildorrery, with the Ballyhouras to the north and the Galtees to the east, the location was picture perfect. A large three story mansion, that took ten years to complete, was built on the estate. Money was no problem, the Bowens had it all. They would be the last Anglo Irish to enjoy supremacy and power over the people.

The Bowens were originally Welsh and came to Ireland during the 17th century. The first Henry Bowen came to Ireland as a colonel in Cromwell’s army. The story goes that he brought with him a pair of hawks, one of whom was killed by Cromwell. To make amends Cromwell promised Bowen as much land as the hawk would fly over. The hawk circled 800 acres of the finest land in County Cork and this was to become Bowen’s Court estate. Colonel Bowen set up home in a castle by the banks of the Farahy River.

It was one of his descendants who built Bowen’s Court on the other side of the river in 1775: a beautiful Italianate mansion, with very large windows that as Elizabeth Bowen said ‘let in lots of light’.

Ireland was dotted with large houses like the one in Farrahy. Some stood the test of time, while others were destroyed in the 1920s, such was the hatred for the Landlord. During the famine, the Bowens opened a soup kitchen to feed the starving. Elizabeth Bowen credits that act of kindness by her ancestors to the saving of Bowen's Court. The calamity that was the famine heralded the end of Landlords, as the tenants either died or emigrated, resulting in rents drying up.

Bowen's Court gave employment to the local people, as a large staff was required to keep the big wheel turning. Cooks, cleaners, maids, gardeners and stable boys were all working out flat. Of course, a ladies maid was also employed. It was an "upstairs downstairs" era. The world revolved around the running of The Big House. The silver breakfast trays, the good china - only the best was good enough.

“Places are peopled with such people”

“Nothing can happen nowhere. The locale of the happening always colours the happening and often to a degree shapes it.”

These two quotations from the writings of Elizabeth Bowen illustrate how she frequently examines the interaction of people and places and the influence each has on the other. All her books are to an extent, explorations of identity and belonging. Perhaps her fascination with places is a consequence of her Anglo-Irish heritage and her self-confessed ambiguous identity. She herself said that the only place she felt truly at home was in the middle of the Irish sea! Kildorrery and Bowen’s Court were places that played a major part both in her life and in her writings.

Elizabeth Bowen was born in Dublin in 1899. It is said that a jig was danced on the table at Bowen’s Court when news broke of her arrival. When she was six weeks old she was brought to Bowen’s Court for the first time and placed in the nursery over the drawing-room, which was to remain her bedroom until she married. Elizabeth was educated in England but spent her summers in Bowen's Court. She loved the freedom of the countryside.

Although privileged as an only child, her life was, nonetheless, full of tragedy. Her father, Robert Bowen, a barrister by profession who practiced in Dublin, was diagnosed with mental illness when Elizabeth was still quite young, and she and her mother were advised to live apart from him. They lived at first in Dublin and then in England.

When she was in her early teens, her mother died of cancer, her father remarried and with the new Lady at Bowen's Court, Elizabeth was subsequently fostered out to a succession of relatives. The shock of her mother's death cast a giant shadow over the young girl and Elizabeth developed a stammer that you remain with her for the rest of her life.

Elizabeth was twenty and living in London when she began to write. Her first book of short stories was published in 1923. In the same year she married Alan Cameron, Secretary for Education to the City of Oxford. She had found perfect bliss with her new husband. Around this time, she would go on to become a well-known novelist. Her novels include ‘The Hotel’, ‘The Last September’, ‘The House in Paris’, and ‘The Death of the Heart’.

Elizabeth Bowen inherited Bowen’s Court in 1930. Apart from the war years, which she spent in London, her summers were always spent at Bowen’s Court and it was always full of visitors. She loved to host dinner parties, to dance, to eat and to drink. The Duhallow Hunt Ball was sometimes held in Bowen’s Court, when she would open all the windows so that the local people could enjoy the music.

But things "they were a changing". The Landlord's grip in Ireland was slipping. The new Republic was beginning to govern itself. Factories were being built, giving employment and a decent wage to the people.

The North Cork landscape and a thinly disguised Bowen’s Court is used as a background for her novel, ‘The Last September’. Made into a film for her centenary in 1999, directed by Deborah Warner and starring Fiona Shaw, the setting is the ‘troubles’ of the 1920’s and tells the story of an Anglo-Irish family living at ‘the big house’. The family finds itself in a rather equivocal position - interest and tradition should bind them to the British but affection ties them to the now resistant people of the surrounding countryside. Many paradoxes are presented. Tennis parties and dances go on while ambushing and burnings occur. Soldiers socialise with young women and enjoy themselves and shortly afterwards they patrol the countryside armed and ready for conflict. Bowen cleverly explores the effects of this transitional period in Irish history on her own class. While the Anglo-Irish attempt to hold on to the old order, fate and time hurdle them towards change.

A similar theme is found in ‘Bowen’s Court’ which was published in 1942. Here she gives an account of her family history and again tackles the vexed subject of Anglo-Irish identity. Elizabeth is buried in Farahy churchyard with her husband, Alan Cameron, between the graves of her father and her aunt Sarah up at the top of the churchyard, facing the door of the church. At the north-west corner is the Famine plot where the bodies were buried in an unmarked grave during the great famine.

Elizabetg and Alan enjoyed life in Farrahy. Elizabeth visited Kildorrery village regularly and was well respected by the locals. Bowen's Court often came alive after dark as Elizabeth and Alan hosted dinner parties for fellow writers and artists. Her novels were selling well and she was in a good place in her life.

Sadness was to set in again when Alan Cameron died suddenly in his sleep in 1952. His death was the killer blow for Elizabeth. Without Alan's guiding hand, she found it increasingly difficult to maintain the house and finally sold it in 1959. She told no-one of her plans. When her relations heard about the sale they came straight to Kildorrery, with the intention of offering financial assistance, but it was too late. Sadly the house was demolished by its new owner in 1960, simply a victim of the economic conditions of the time. Had it survived another decade it would probably have become a visitor attraction as country houses became very popular with tourists and domestic visitors in the 1970s. All that remains today is the walls of the 2.5 acre garden.

After the sale of the house, Elizabeth had moved back to England. Her health deteriorated and she died there. Her body was brought back to Farrahy for burial, beside her ancestors in the family graveyard. The Bowen name had run its course.

In 1887, William Gates, son of Charles Gates, owner of The West Surrey Central Dairy Company in Guildford which produced Britain's first powdered milk, was sent to establish a creamery in Kildorrery. William, a dentist, had not previously been in the business but it was thought that 'being delicate' the fresh air would be good for his health.

Anthony Carroll, a solicitor in Fermoy and landlord of an old police barracks in Kildorrery, persuaded William to convert the site and put his creamery there. There was a small property between the site and O'Mahoney's on the Limerick Road, which William purchased, on which they built a cold room.

William took board and lodgings with Eliza Roche, a local shopkeeper, where a young apprentice, Kate Fitzgerald, was working off her father's debt for groceries. Her potential ability was recognised by William, who taught her bookkeeping. Some eleven years later, when she was 24, he employed her as bookkeeper.

In 1929, the name was changed to Cow & Gate and the well-known cow looking through the gate logo was adopted. From 1887 to the 30th of April 1954, Cow and Gate played a key role in Kildorrery's economic life, with farmers bringing their milk to the creamery and visiting a grain crushing plant adjacent to it.

William Gates quickly perfected the art of mechanically extracting cream from milk and his cream factory here was soon regarded as the leading example in the south of Ireland. The cream produced in Kildorrery was sent in 20 gallon churns to Ballyhooley railway station by horse and cart for transportation to Rosslare by train. From there it went to Fishguard by boat and then on to Guildford. Each churn has a plate on it which read: "Full to Guildford - Empty to Kildorrery." The fresh cream products produced here were of such a high quality they soon found their way to onto the table of Buckingham Palace.

By 1900 the company was thriving and the enterprising Gates brothers decided to invest in drying equipment to produce powder milk from the skimmed milk that was left over from the creaming process. Soon orders were coming in from all over the U.K. for their new product but it was from the baking and catering trade mainly.

Within a few years a doctor in Leicester, who had began research into the benefits of feeding babies dried powder milk, ordered a large quantity of powder and so began a new phase for this innovative company.

When William began to practice his dentistry again, Kate managed the creamery. She was invited to live with the family and kept accounts for not only the creamery but the dental practice and the farm. She became one of the strongest influences in Cow & Gate Ireland, having worked in the creamery for most of her life. Before William Gates died in 1933, he appointed Kate Fitzgerald Joint Managing Director together with his son, Charles Howard (Jim) Gates. For the next 29 years, meticulous and highly respected Kate effectively ran the business. Jim Gates died in 1954 and Kate retired on full pay in 1962 when Cow & Gate presented her with a medal marking 64 years service. She died in 1964 'independent to the end' of her 90 years.

By 1956, Cow & Gate had proposed to build a factory in Kildorrery but it never happened and the factory was built in Mallow instead. When local farmers voted to join Mitchelstown Co-op, they sold the creamery to the Co-op and so ended a 70-year Cow & Gate association with the village, but a new era began for the farmers of the area. (See the next section on Mitchelstown Co-op for more details.)

When William Gates arrived in Ireland in 1887 even though he came to open a dairy creamery, he was a qualified dentist, and he brought his dentistry equipment with him. He offered a free service of extraction only from his home in the area and he often came home from work to a queue of tortured souls waiting to have a tooth extracted. He used to joke ‘I have spilt more Irish blood than any other Englishman in history’. He later developed a more serious dental practice and opened branches in other local towns. He was involved in the setting up of the Cork Dental school and hospital and was a member of the voluntary teaching staff.

William Gates is buried in Farahy Graveyard alongside Elizabeth Bowen, who he was a good friend of.

Cow & Gate Creamery before it was demolished

Milk carts in Kildorrery

Mitchelstown Co-op was founded in 1919 by local farmers who pooled their resources together to buy seeds directly from a wholesaler and thereby cut out the middle men who had for a long time profiteered out of farmers. Within weeks of their first purchase, the same farmers decided to set up a co-operative shop in the town and if this was a success they would build a creamery by re-investing the profits of the shop. It was a resounding success and by 1925 they opened a creamery on the Clonmel Rd.

The creamery at first had a daily intake of 22,000 litres of milk and its main product was butter. Within a short few years the intake increased to 130,000 litres when they opened branches it several other villages in the area.

When World War II ended, Europe was in ruins and there was a great shortage of agricultural produce. Most of the Irish surplus went to Britain. In the pre-war years, Britain had started a programme to eradicate tuberculosis in cattle and post-war, these efforts were intensified. This had its repercussions in Ireland as it involved having all the milk for direct consumption and manufacture pasteurised.

The Department of Agriculture inspected creameries and found that Cow & Gate creamery in Kildorrery was not up to standard. This meant that if Cow & Gate was to stay in Kildorrery, it would have to spend a considerable amount of money in bringing their premises up to standard, as the building was very old. The decision taken at Guildford was that it would be uneconomical - so that brought an end to the business in Kildorrery.

Cow & Gate had always traded with Ballyclough Co-op but Mitchelstown Co-op were very interested in taking over the operations at Cow & Gate. There were many meetings regarding the take over held in the Parish Hall (Town Hall) and in O'Dwyers Hall on the Limerick Road. A vote was eventually taken by the milk suppliers and the vast majority decided to go with Mitchelstown Co-op.

Cow & Gate was sold to Mitchelstown Co-op and they opened on 1st of May 1954. Mitchelstown Co-op also bought the land where the Irish Tree Centre is now, mainly to solve the problem of the 'waste-washing' from the creamery flowing down through the land. The also grazed cattle on the land.

In 1954 Mitchelstown Co-op also bought an acre of land on the Fermoy Road from Carroll's where the Community Car Park is today. A new creamery was built on this site during 1954/1955 and it opened for business in Oct 1955. The store was built in 1956, where Mitchelstown Co-op operated their farm supplies business out of, selling fertilizers, feed, fuel, coal and hardward.

In the 1950s, Mitchelstown Co-op had their own cheesemaking operation. ‘Calvita’, ‘Galtee Cheese’, 'Three Counties', 'Whitethorn', and 'Mandeville' were well known brands then. The system that was used in Kildorrery of separating the cream from milk ceased on 31st Aug 1978. It was more economical to collect it in a large tank and cool it in a new cooling system, which was actually built outside the creamery building itself. Kildorrery became a collection point only, and the milk was transported to Mitchelstown by bulk tankers. Bulk tankers had become common by then and collcted the milk from many farms, but not all farms were able to comply with the conditions of bulk tank collection, so instead continued to deliver their milk daily to the collection point in churns and mobile tankers.

In 1990 Mitchelstown Co-op amalgamated with their Mallow counterparts Ballyclough Co-op to form Dairygold, one of the largest dairy companies in Ireland. The creameries and farm supply stores in the villages have all now closed but Dairygold continues to prosper and grow and the food produced in this fertile valley is exported to every corner of the globe and not just European markets but Asia and Africa too.

The Creamery before restoration

The Creamery after restoration

The Store before restoration

The Store after restoration

On Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, a group of Irish nationalists proclaimed the establishment of the Irish Republic and, along with some 1,600 followers, staged a rebellion against the British government in Ireland.

The Easter Rising was intended to take place across Ireland; however, various circumstances resulted in it being carried out primarily in Dublin.

On April 24, 1916, the rebel leaders and their followers (whose numbers reached some 1,600 people over the course of the insurrection, and many of whom were members of a nationalist organization called the Irish Volunteers, or a small radical militia group, the Irish Citizen Army), seized the city’s general post office and other strategic locations.

Early that afternoon, from the steps of the post office, Patrick Pearse (1879-1916), one of the uprising’s leaders, read a proclamation declaring Ireland an independent republic and stating that a provisional government had been appointed.

Despite the rebels’ hopes, the public did not rise to support them. The British government soon declared martial law in Ireland, and in less than a week the rebels were crushed by the government forces sent against them. Some 450 people were killed and more than 2,000 others, many of them civilians, were wounded in the violence, which also destroyed much of the Dublin city center.

Initially, many Irish people resented the rebels for the destruction and death caused by the uprising. However, in May, 15 leaders of the uprising were executed by firing squad. More than 3,000 people suspected of supporting the uprising, directly or indirectly, were arrested, and some 1,800 were sent to England and imprisoned there without trial.

The rushed executions, mass arrests and martial law (which remained in effect through the fall of 1916), fueled public resentment toward the British and were among the factors that helped build support for the rebels and the movement for Irish independence.

In the 1918 general election to the parliament of the United Kingdom, the Sinn Fein political party (whose goal was to establish a republic) won a majority of the Irish seats.

The Sinn Fein members then refused to sit in the UK Parliament, and in January 1919 met in Dublin to convene a single chamber parliament and declare Ireland’s independence. The Irish Republican Army then launched a guerrilla war against the British government and its forces in Ireland.

Following a July 1921 cease-fire, the two sides signed a treaty in December that called for the establishment of the Irish Free State, a self-governing nation of the British Commonwealth, the following year.

Ireland’s six northern counties opted out of the Free State and remained with the United Kingdom. The fully independent Republic of Ireland (consisting of the 26 counties in the southern and western part of the island) was formally proclaimed on Easter Monday, April 18, 1949.

Source: History.com

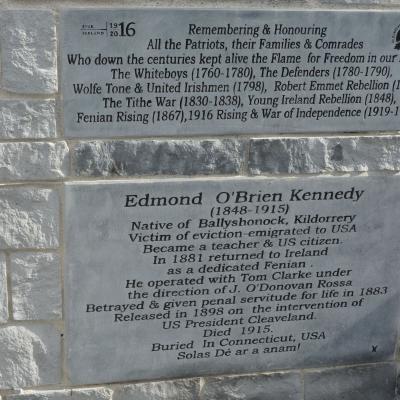

Memorial & Remembrance Garden in Village Park

Recommended Reading

Proclaiming a Republic: The 1916 Rising

National Museum of Ireland

The War of Independence 1919-1921 "A Short History"

Atlas of the Irish Revolution, Resources for Schools

UCC College of Arts, Celtic Studies and Social Sciences

The Irish War of Independence

National Museum of Ireland

War of Independence: the bloodiest six months

The Irish Times 3 June 2020

‘The War of Independence in Limerick, 1912-1921’

Tom Toomey

‘Honouring the Men and Women. The War of Independence Volunteers in East & Mid Limerick’ Tom Toomey and The Knocklong History Group

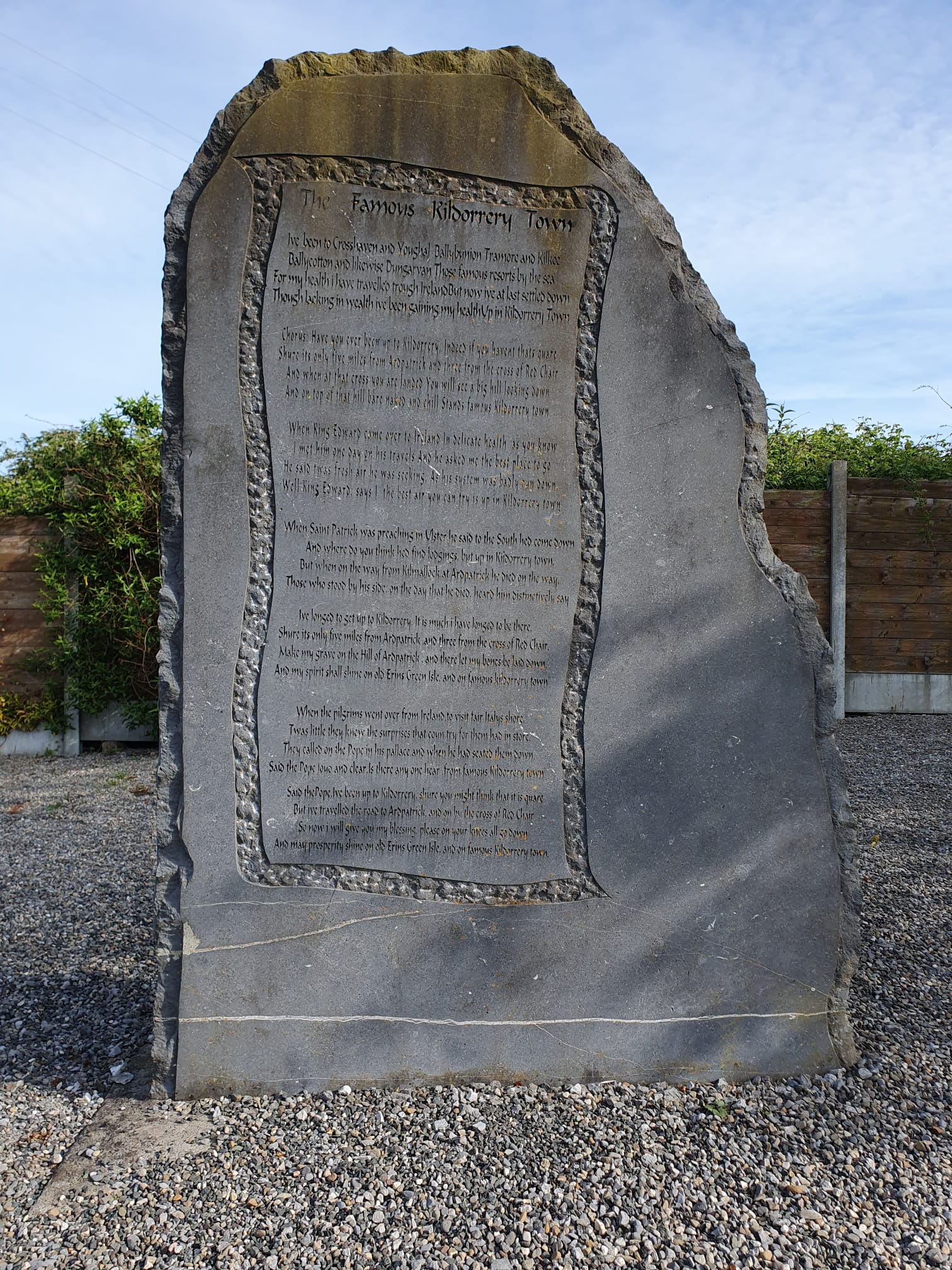

Famous Kildorrery Town

I've been to Crosshaven and Youghal

Ballybunion, Tramore and Kilkee

Ballycotton and likewise Dungarvan

Those famous resorts by the sea

For my health I have traveled through Ireland

But now I've at last settled down

Though lacking in wealth I've been gaining my health

Up in Kildorrery town

Have up ever been up to Kildorrery

Indeed if you haven't that's quare

Sure it's only five miles from Ardpatrick

And three from the cross of Red Chair

And when at that cross you are landed

You will see a big hill looking down

And on top of that hill bare naked and chill

Stands famous Kildorrery town

When King Edward came over to Ireland

In delicate health as you know

I met him one day in his travels

And he asked me the best place to go

He said twas fresh air he was seeking

As his system was badly run down

"Well King Edward" says I "the best air you can try

Is up in Kildorrery town"

When Saint Patrick was preaching in Ulster

He said to the south he'd come down

And where do you think he'd find lodgings

But up in Kildorrery town

But when on the way from Kilmallock

At Ardpatrick he died on the way

Those who stood by his side on the day that he died

Heard him distinctively say:

"Ah I've longed to get up to Kildorrery

It is much I have longed to be there

Sure it's only five miles from Ardpatrick

And three from the cross of Red Chair

Make my grave on the Hill of Ardpatrick

And there let my bones be laid down

And my spirit shall shine on old Erin's Green Isle

And on famous Kildorrery town"

When the pilgrims went over from Ireland

To visit fair Italy's shore

Twas little they knew the surprises

That country for them had in store

They called to the Pope in his Palace

And when he had seated them down

Said the Pope loud and clear "Is there anyone here

From famous Kildorrery town?"

Said the Pope "I've been to Kildorrery

Sure you might think that is quare

But I traveled the road to Ardpatrick

And on by the cross of Red Chair

So now I will give you my blessing

Please on your knees all go down

And may prosperity shine on Erin's Green Isle

And on famous Kildorrery"

Have up ever been up to Kildorrery

Indeed if you haven't that's quare

Sure it's only five miles from Ardpatrick

And three from the cross of Red Chair

And when at that cross you are landed

You will see a big hill looking down

And on top of that hill bare naked and chill

Stands famous Kildorrery town

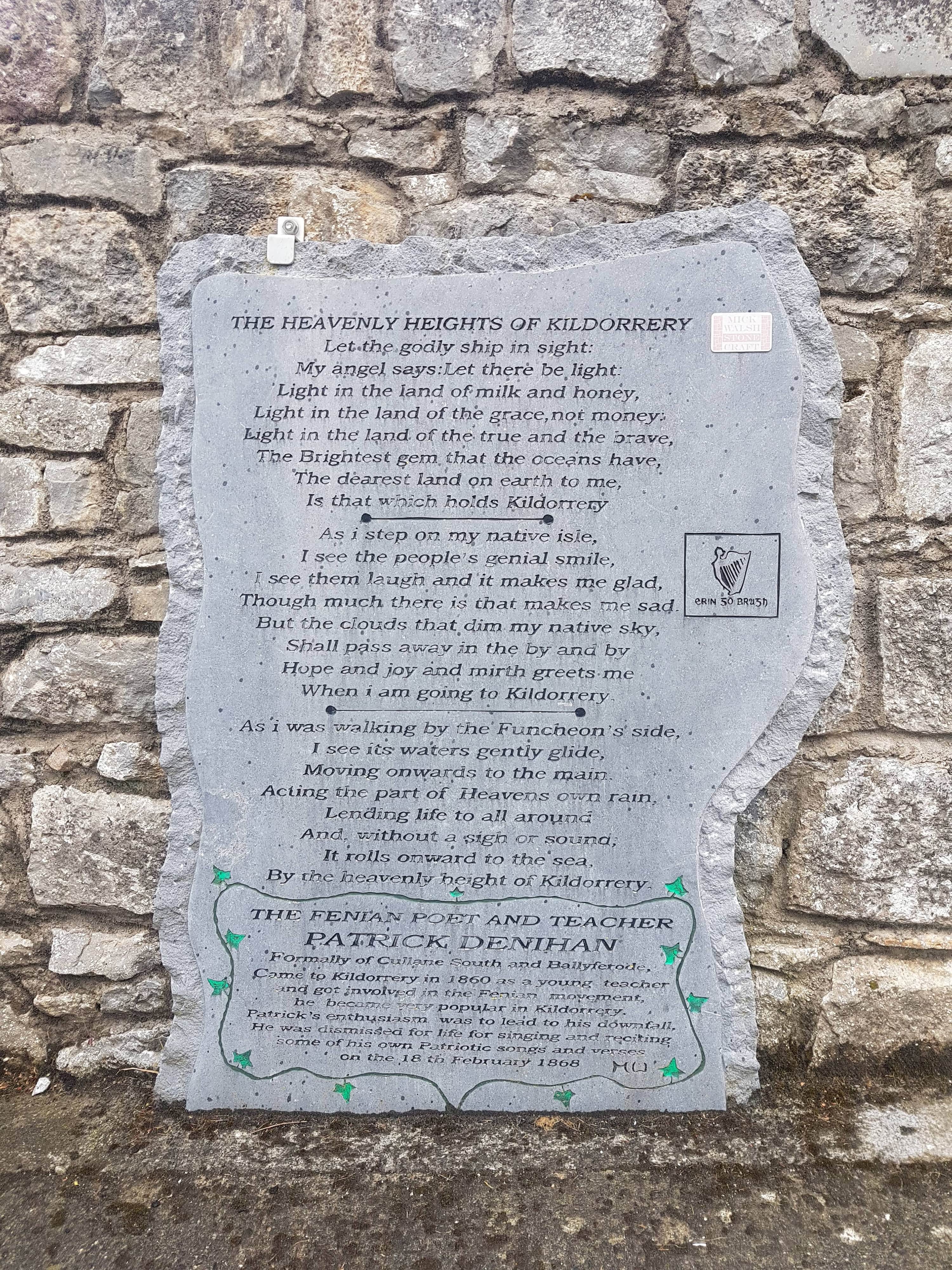

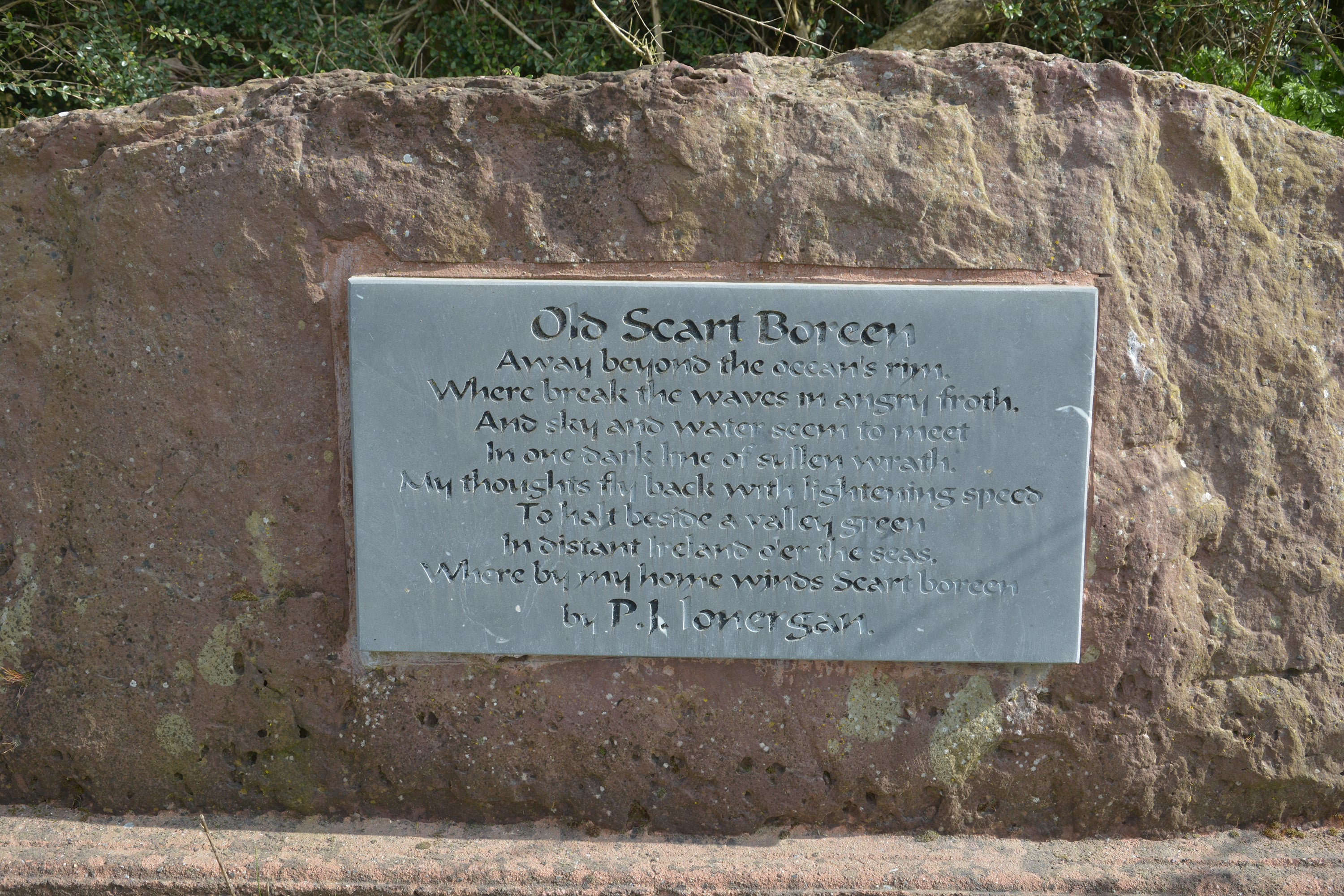

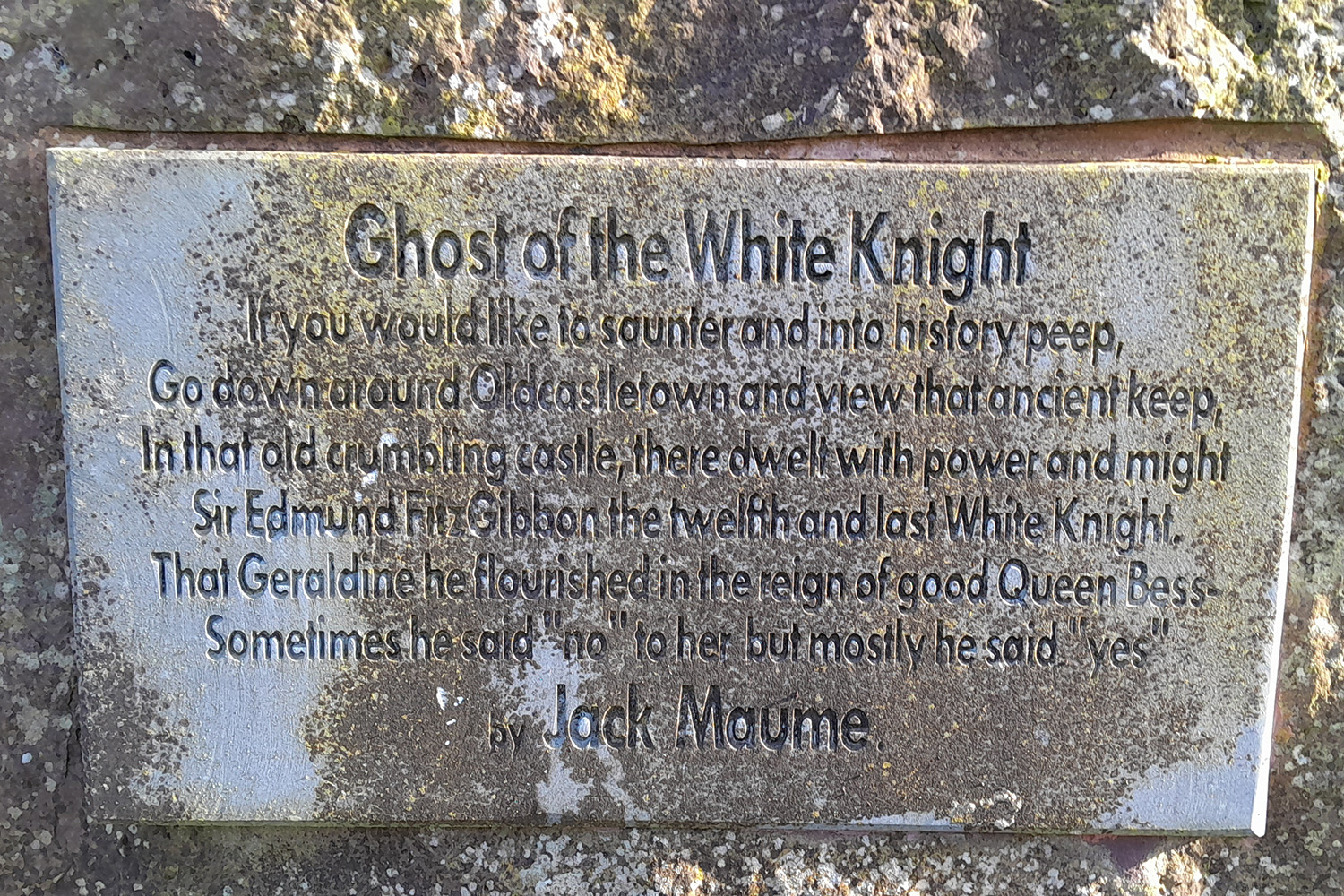

The poets of Kildorrery were commemorated in a series of stones that were sculpted by local man Mike Walsh. These were men of rare talent with an interest in Irish culture, music, history, literature and all things Irish and had the gift of expressing this in their poetry and writings.

'Kings of ancient Erin - Three

Indulged here 'neath an old oak tree

Long ere the shelter on this scene

"O tell us" said they to their Druid,

"Reveal this hillock's future good"

Replying, he proudly looked around

"Every good shall here be found - Riches, people living well,

Ye Kings of Erin, time will tell".

Today this spot seems to wear a crown,

Overlooking vales, a lovely town

With splendid church where once hath stood

Nough but a dark and drear oak wood'

- Eugene Geary, 'Kildorrery Town', 1901-1956